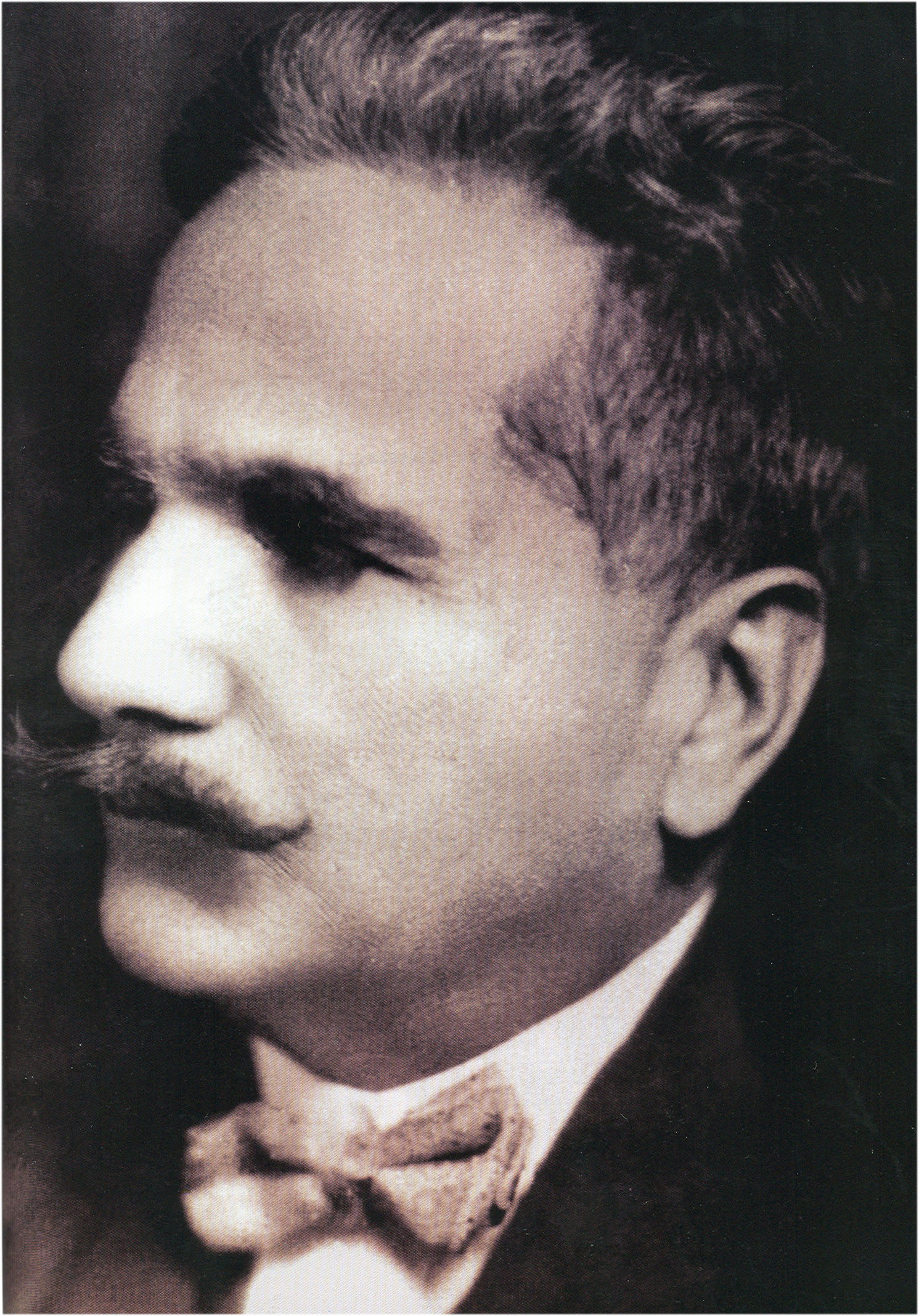

Biography

Iqbal was born on 9 November 1877 in an ethnic Kashmiri family in Sialkot within the Punjab Province of

British India (now in Pakistan). His family was Kashmiri Pandit (of the Sapru clan) that converted to

Islam in the 15th century and which traced its roots back to a south Kashmir village in Kulgam. In the

19th century, when the Sikh Empire was conquering Kashmir, his grandfather's family migrated to Punjab.

Iqbal's grandfather was an eighth cousin of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, an important lawyer and freedom fighter

who would eventually become an admirer of Iqbal. Iqbal often mentioned and commemorated his Kashmiri

lineage in his writings. According to scholar Annemarie Schimmel, Iqbal often wrote about his being "a son

of Kashmiri-Brahmans but (being) acquainted with the wisdom of Rumi and Tabriz." Iqbal's father, Sheikh

Noor Muhammad (died 1930), was a tailor, not formally educated, but a religious man. Iqbal's mother Imam

Bibi, a Kashmiri from Sambrial, was described as a polite and humble woman who helped the poor and her

neighbours with their problems. She died on 9 November 1914 in Sialkot.

Iqbal was four years old when he was sent to a mosque to receive instruction in reading the Qur'an.He

learned the Arabic language from his teacher, Syed Mir Hassan, the head of the madrasa and professor of

Arabic at Scotch Mission College in Sialkot, where he matriculated in 1893. He received an Intermediate

level with the Faculty of Arts diploma in 1895. The same year he enrolled at Government College

University, where he obtained his Bachelor of Arts in philosophy, English literature and Arabic in 1897,

and won the Khan Bahadurddin F.S. Jalaluddin medal as he performed well in Arabic. In 1899, he received

his Master of Arts degree from the same college and won first place in philosophy in the University of the

Punjab.

Iqbal married three times under different circumstances. His first marriage was in 1895 when he was 18

years old. His bride, Karim Bibi, was the daughter of a physician, Khan Bahadur Ata Muhammad Khan, a

Gujurati physician. Her sister was the mother of director and music composer Khwaja Khurshid Anwar. Their

families arranged the marriage, and the couple had two children; a daughter, Miraj Begum (1895–1915), and

a son, Aftab Iqbal (1899–1979), who became a barrister. Another son is said to have died after birth in

1901. Iqbal and Karim Bibi separated somewhere between 1910 and 1913. Despite this, he continued to

financially support her till his death. Iqbal's second marriage was with Mukhtar Begum, and it was held in

December 1914, shortly after the death of Iqbal's mother the previous November. They had a son, but both

the mother and son died shortly after birth in 1924. Later, Iqbal married Sardar Begum, and they became

the parents of a son, Javed Iqbal (1924–2015), who became Senior Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan,

and a daughter, Muneera Bano (born 1930). One of Muneera's sons is the philanthropist-cum-socialite Yousuf

Salahuddin.

Iqbal was influenced by the teachings of Sir Thomas Arnold, his philosophy teacher at Government College

Lahore, to pursue higher education in the West. In 1905, he travelled to England for that purpose. While

already acquainted with Friedrich Nietzsche and Henri Bergson, Iqbal would discover Rumi slightly before

his departure to England, and he would teach the Masnavi to his friend Swami Rama Tirtha, who in return

would teach him Sanskrit. Iqbal qualified for a scholarship from Trinity College, University of Cambridge,

and obtained a Bachelor of Arts in 1906. This B.A. degree in London, made him eligible, to practice as an

advocate, as it was being practiced those days. In the same year he was called to the bar as a barrister

at Lincoln's Inn. In 1907, Iqbal moved to Germany to pursue his doctoral studies, and earned a Doctor of

Philosophy degree from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1908. Working under the guidance of

Friedrich Hommel, Iqbal's doctoral thesis was entitled The Development of Metaphysics in Persia. In 1907,

he had a close friendship with the writer Atiya Fyzee in both Britain and Germany. Atiya would later

publish their correspondence. While Iqbal was in Heidelberg in 1907, his German professor Emma Wegenast

taught him about Goethe's Faust, Heine and Nietzsche. He mastered German in three months. During his study

in Europe, Iqbal began to write poetry in Persian. He preferred to write in this language because doing so

made it easier to express his thoughts. He would write continuously in Persian throughout his life.

Iqbal began his career as a reader of Arabic after completing his Master of Arts degree in 1899, at

Oriental College and shortly afterward was selected as a junior professor of philosophy at Government

College Lahore, where he had also been a student in the past. He worked there until he left for England in

1905. In 1907 he went to Germany for PhD In 1908, he returned from Germany and joined the same college

again as a professor of philosophy and English literature. In the same period Iqbal began practising law

at the Chief Court of Lahore, but he soon quit law practice and devoted himself to literary works,

becoming an active member of Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam. In 1919, he became the general secretary of the

same organisation. Iqbal's thoughts in his work primarily focus on the spiritual direction and development

of human society, centered around experiences from his travels and stays in Western Europe and the Middle

East. He was profoundly influenced by Western philosophers such as Nietzsche, Bergson, and Goethe. He also

closely worked with Ibrahim Hisham during his stay at the Aligarh Muslim University. The poetry and

philosophy of Rumi strongly influenced Iqbal. Deeply grounded in religion since childhood, Iqbal began

concentrating intensely on the study of Islam, the culture and history of Islamic civilisation and its

political future, while embracing Rumi as "his guide". Iqbal's works focus on reminding his readers of the

past glories of Islamic civilisation and delivering the message of a pure, spiritual focus on Islam as a

source for socio-political liberation and greatness. Iqbal denounced political divisions within and

amongst Muslim nations, and frequently alluded to and spoke in terms of the global Muslim community or the

Ummah. Iqbal's poetry was translated into many European languages in the early part of the 20th century.

Iqbal's Asrar-i-Khudi and Javed Nama were translated into English by R. A. Nicholson and A. J. Arberry,

respectively.

Works

Iqbal first became interested in national affairs in his youth. He received considerable recognition from

the Punjabi elite after his return from England in 1908, and he was closely associated with Mian Muhammad

Shafi. When the All-India Muslim League was expanded to the provincial level, and Shafi received a

significant role in the structural organisation of the Punjab Muslim League, Iqbal was made one of the

first three joint secretaries along with Shaikh Abdul Aziz and Maulvi Mahbub Alam. While dividing his time

between law practice and poetry, Iqbal remained active in the Muslim League. He did not support Indian

involvement in World War I and stayed in close touch with Muslim political leaders such as Mohammad Ali

Jouhar and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He was a critic of the mainstream Indian National Congress, which he

regarded as dominated by Hindus, and was disappointed with the League when, during the 1920s, it was

absorbed in factional divides between the pro-British group led by Shafi and the centrist group led by

Jinnah. He was active in the Khilafat Movement, and was among the founding fathers of Jamia Millia Islamia

which was established at Aligarh in October 1920. He was also given the offer of being the first

vice-chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia by Mahatma Gandhi, which he refused. In November 1926, with the

encouragement of friends and supporters, Iqbal contested the election for a seat in the Punjab Legislative

Assembly from the Muslim district of Lahore, and defeated his opponent by a margin of 3,177 votes. He

supported the constitutional proposals presented by Jinnah to guarantee Muslim political rights and

influence in a coalition with the Congress and worked with Aga Khan and other Muslim leaders to mend the

factional divisions and achieve unity in the Muslim League. While in Lahore he was a friend of Abdul

Sattar Ranjoor.

Iqbal's six English lectures were published in Lahore in 1930, and then by the Oxford University Press in

1934 in the

book The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. The lectures had been delivered at Madras,

Hyderabad and Aligarh.

These lectures dwell on the role of Islam as a religion and as a political and legal philosophy in the

modern age. In

these lectures Iqbal firmly rejects the political attitudes and conduct of Muslim politicians, whom he saw

as morally

misguided, attached to power and without any standing with the Muslim masses. Iqbal expressed fears that

not only would

secularism weaken the spiritual foundations of Islam and Muslim society but that India's Hindu-majority

population would

crowd out Muslim heritage, culture, and political influence. In his travels to Egypt, Afghanistan, Iran,

and Turkey, he

promoted ideas of greater Islamic political co-operation and unity, calling for the shedding of

nationalist differences.

He also speculated on different political arrangements to guarantee Muslim political power; in a dialogue

with Dr. B. R.

Ambedkar, Iqbal expressed his desire to see Indian provinces as autonomous units under the direct control

of the British

government and with no central Indian government. He envisaged autonomous Muslim regions in India. Under a

single Indian

union, he feared for Muslims, who would suffer in many respects, especially concerning their existentially

separate

entity as Muslims. Iqbal was elected president of the Muslim League in 1930 at its session in Allahabad in

the United

Provinces, as well as for the session in Lahore in 1932. In his presidential address on 29 December 1930

he outlined a

vision of an independent state for Muslim-majority provinces in north-western India: I would like to see

the Punjab,

North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within

the British

Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated Northwest Indian Muslim state

appears to me to be

the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of Northwest India. In his speech, Iqbal emphasised that,

unlike

Christianity, Islam came with "legal concepts" with "civic significance", with its "religious ideals"

considered as

inseparable from social order: "Therefore, if it means a displacement of the Islamic principle of

solidarity, the

construction of a policy on national lines, is simply unthinkable to a Muslim." Iqbal thus stressed not

only the need

for the political unity of Muslim communities but the undesirability of blending the Muslim population

into a wider

society not based on Islamic principles.He thus became the first politician to articulate what would

become known as the

Two-nation theory—that Muslims are a distinct nation and thus deserve political independence from other

regions and

communities of India. Even as he rejected secularism and nationalism he would not elucidate or specify if

his ideal

Islamic state would be a theocracy, and criticised the "intellectual attitudes" of Islamic scholars

(ulema) as having

"reduced the Law of Islam practically to the state of immobility". The latter part of Iqbal's life was

concentrated on

political activity. He travelled across Europe and West Asia to garner political and financial support for

the League.

He reiterated the ideas of his 1932 address, and, during the third Round Table Conference, he opposed the

Congress and

proposals for transfer of power without considerable autonomy or independence for Muslim provinces. He

would serve as

president of the Punjab Muslim League, and would deliver speeches and publish articles in an attempt to

rally Muslims

across India as a single political entity. Iqbal consistently criticised feudal classes in Punjab as well

as Muslim

politicians opposed to the League. Many accounts of Iqbal's frustration toward Congress leadership were

also pivotal in

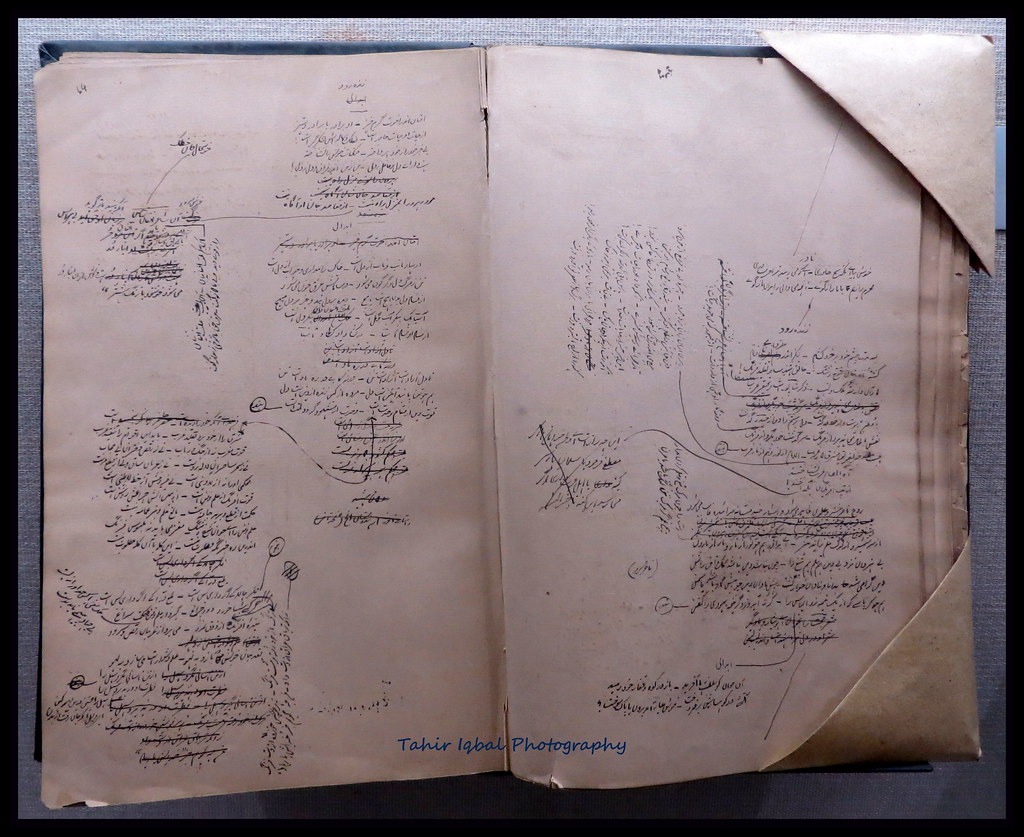

providing a vision for the two-nation theory. Patron of Tolu-e-Islam Copy of the first issue of

Tolu-e-Islam Iqbal was

the first patron of Tolu-e-Islam, a historical, political, religious and cultural journal of the Muslims

of British

India. For a long time, Iqbal wanted a journal to propagate his ideas and the aims and objectives of the

All India

Muslim League. In 1935, according to his instructions, Syed Nazeer Niazi initiated and edited the journal,

named after

Iqbal's poem "Tulu'i Islam". Niazi dedicated the first issue of the journal to Iqbal. The journal would

play an

important role in the Pakistan movement. Later, the journal was continued by Ghulam Ahmed Pervez, who had

contributed

many articles in its early editions.

Literature

Iqbal's poetic works are written primarily in Persian rather than Urdu. Among his 12,000 verses of poetry,

about 7,000 verses are in Persian. In 1915, he published his first collection of poetry, the Asrar-i-Khudi

اسرارِ خودی (Secrets of the Self) in Persian. The poems emphasize the spirit and self from a religious

perspective. Many critics have called this Iqbal's finest poetic work. In Asrar-i-Khudi, Iqbal explains

his philosophy of "Khudi", or "Self". Iqbal's use of the term "Khudi" is synonymous with the word "Rooh"

used in the Quran for a divine spark which is present in every human being, and was said by Iqbal to be

present in Adam, for which God ordered all of the angels to prostrate in front of Adam. Iqbal condemns

self-destruction. For him, the aim of life is self-realization and self-knowledge. He charts the stages

through which the "Self" has to pass before finally arriving at its point of perfection, enabling the

knower of the "Self" to become a vice-regent of God. In his Rumuz-i-Bekhudi رموزِ بیخودی (Hints of

Selflessness), Iqbal seeks to prove the Islamic way of life is the best code of conduct for a nation's

viability. A person must keep his characteristics intact, he asserts, but once this is achieved, he should

sacrifice his ambitions for the needs of the nation. Man cannot realise the "Self" outside of society.

Published in 1917, this group of poems has as its main themes the ideal community, Islamic ethical and

social principles, and the relationship between the individual and society. Although he supports Islam,

Iqbal also recognizes the positive aspects of other religions. Rumuz-i-Bekhudi complements the emphasis on

the self in Asrar-e-Khudi and the two collections are often put in the same volume under the title

Asrar-i-Rumuz (Hinting Secrets). It is addressed to the world's Muslims. Iqbal's 1924 publication, the

Payam-e-Mashriq پیامِ مشرق (The Message of the East), is closely connected to the West-östlicher Diwan by

the German poet Goethe. Goethe bemoans the West having become too materialistic in outlook, and expects

the East will provide a message of hope to resuscitate spiritual values. Iqbal styles his work as a

reminder to the West of the importance of morality, religion, and civilisation by underlining the need for

cultivating feeling, ardor, and dynamism. He asserts that an individual can never aspire to higher

dimensions unless he learns of the nature of spirituality. In his first visit to Afghanistan, he presented

Payam-e Mashreq to King Amanullah Khan. In it, he admired the uprising of Afghanistan against the British

Empire. In 1933, he was officially invited to Afghanistan to join the meetings regarding the establishment

of Kabul University. The Zabur-e-Ajam زبورِ عجم (Persian Psalms), published in 1927, includes the poems

"Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed" ("Garden of New Secrets") and "Bandagi Nama" ("Book of Slavery"). In

"Gulshan-e-Raz-e-Jadeed", Iqbal first poses questions, then answers them with the help of ancient and

modern insight. "Bandagi Nama" denounces slavery and attempts to explain the spirit behind the fine arts

of enslaved societies. Here, as in other books, Iqbal insists on remembering the past, doing well in the

present and preparing for the future, while emphasizing love, enthusiasm and energy to fulfill the ideal

life. Iqbal's 1932 work, the Javed Nama جاوید نامہ (Book of Javed), is named after and in a manner

addressed to his son, who is featured in the poems. It follows the examples of the works of Ibn Arabi and

Dante's The Divine Comedy, through mystical and exaggerated depictions across time. Iqbal depicts himself

as Zinda Rud ("A stream full of life") guided by Rumi, "the master", through various heavens and spheres

and has the honour of approaching divinity and coming in contact with divine illuminations. In a passage

reliving a historical period, Iqbal condemns the Muslims who were instrumental in the defeat and death of

Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula of Bengal and Tipu Sultan of Mysore by betraying them for the benefit of the British

colonists, and thus delivering their country to the shackles of slavery. In the end, by addressing his son

Javid, he speaks to the young people at large, and guides the "new generation". Pas Chih Bayed Kard Ay

Aqwam-e-Sharq پس چہ باید کرد اے اقوامِ شرق includes the poem "Musafir" مسافر ("The Traveller"). Again,

Iqbal depicts Rumi as a character and gives an exposition of the mysteries of Islamic laws and Sufi

perceptions. Iqbal laments the dissension and disunity among the Indian Muslims as well as Muslim nations.

"Musafir" is an account of one of Iqbal's journeys to Afghanistan, in which the Pashtun people are

counselled to learn the "secret of Islam" and to "build up the self" within themselves. His love of the

Persian language is evident in his works and poetry. He says in one of his poems: گرچہ ہندی در عذوبت شکر

است garchi Hindi dar uzūbat shakkar ast طرز گفتار دري شيرين تر است tarz-i guftar-i Dari shirin tar ast

Translation: Even though in sweetness Hindi* [archaic name for Urdu, lit. "language of India"] is sugar –

(but) speech method in Dari [the variety of Persian in Afghanistan ] is sweeter * Throughout his life,

Iqbal would prefer writing in Persian as he believed it allowed him to fully express philosophical

concepts, and it gave him a wider audience.

Muhammad Iqbal's The Call of the Marching Bell (بانگِ درا, bang-e-dara), his first collection of Urdu

poetry, was published in 1924. It was written in three distinct phases of his life. The poems he wrote up

to 1905—the year he left for England—reflect patriotism and the imagery of nature, including the Urdu

language patriotic "Saare Jahan se Accha", and "Tarana-e-Milli" ("The Song of the Community"). The second

set of poems date from 1905 to 1908, when Iqbal studied in Europe, and dwell upon the nature of European

society, which he emphasised had lost spiritual and religious values. This inspired Iqbal to write poems

on the historical and cultural heritage of Islam and the Muslim community, with a global perspective.

Iqbal urges the entire Muslim community, addressed as the Ummah, to define personal, social and political

existence by the values and teachings of Islam. Iqbal's works were in Persian for most of his career, but

after 1930 his works were mainly in Urdu. His works in this period were often specifically directed at the

Muslim masses of India, with an even stronger emphasis on Islam and Muslim spiritual and political

reawakening. Published in 1935, Bal-e-Jibril بالِ جبریل (Wings of Gabriel) is considered by many critics

as his finest Urdu poetry and was inspired by his visit to Spain, where he visited the monuments and

legacy of the kingdom of the Moors. It consists of ghazals, poems, quatrains and epigrams and carries a

strong sense of religious passion. Zarb-i-Kalim ضربِ کلیم (or The Rod of Moses) is another philosophical

poetry book of Allama Iqbal in Urdu, it was published in 1936, two years before his death. In which he

described as his political manifesto. It was published with the subtitle "A Declaration of War Against the

Present Times. Muhammad Iqbal argues that modern problems are due to the godlessness, materialism, and

injustice of modern civilisation, which feeds on the subjugation and exploitation of weak nations,

especially the Indian Muslims. Iqbal's final work was Armughan-e-Hijaz ارمغانِ حجاز (The Gift of Hijaz),

published posthumously in 1938. The first part contains quatrains in Persian, and the second part contains

some poems and epigrams in Urdu. The Persian quatrains convey the impression that the poet is travelling

through the Hijaz in his imagination. The profundity of ideas and intensity of passion are the salient

features of these short poems. Iqbal's vision of mystical experience is clear in one of his Urdu ghazals,

which was written in London during his student days. Some verses of that ghazal are: At last, the silent

tongue of Hijaz has announced to the ardent ear the tiding That the covenant which had been given to the

desert-[dwellers] is going to be renewed vigorously: The lion who had emerged from the desert and had

toppled the Roman Empire is As I am told by the angels, about to get up again (from his slumbers.) You the

[dwellers] of the West, should know that the world of God is not a shop (of yours). Your imagined pure

gold is about to lose its standard value (as fixed by you). Your civilization will commit suicide with its

own daggers. For a house built on a fragile bark of wood is not longlasting

Iqbal wrote two books, The Development of Metaphysics in Persia (1908) and The Reconstruction of Religious

Thought in Islam (1930), and many letters in the English language. He also wrote a book on Economics that

is now rare. In these, he revealed his thoughts regarding Persian ideology and Islamic Sufism – in

particular, his beliefs that Islamic Sufism activates the searching soul to a superior perception of life.

He also discussed philosophy, God and the meaning of prayer, human spirit and Muslim culture, as well as

other political, social and religious problems. Iqbal was invited to Cambridge to participate in a

conference in 1931, where he expressed his views, including those on the separation of church and state,

to students and other participants: I would like to offer a few pieces of advice to the young men who are

at present studying at Cambridge. ... I advise you to guard against atheism and materialism. The biggest

blunder made by Europe was the separation of Church and State. This deprived their culture of moral soul

and diverted it to atheistic materialism. I had twenty-five years ago seen through the drawbacks of this

civilization and, therefore, had made some prophecies. They had been delivered by my tongue, although I

did not quite understand them. This happened in 1907. ... After six or seven years, my prophecies came

true, word by word. The European war of 1914 was an outcome of the mistakes mentioned above made by the

European nations in the separation of the Church and the State.

Iqbal also wrote some poems in Punjabi, such as "Piyaara Jedi" and "Baba Bakri Wala", which he penned in

1929 on the occasion of his son Javid's birthday. A collection of his Punjabi poetry was put on display at

the Iqbal Manzil in Sialkot.

Gallery

Reference

- Lelyveld, David (2004), "Muhammad Iqbal", in Martin, Richard C. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World: A-L, Macmillan, p. 356, ISBN 978-0-02-865604-5, "Muhammad Iqbal, South Asian poet and ideological innovator, wrote poetry in Urdu and Persian and discursive prose, primarily in English, of particular significance in the formulation of a national ethos for Pakistan.

- Iqbal, Sir Muhammad; Singh, Khushwant (translator); Zakaria, Rafiq (foreword) (1981), Shikwa and Jawab-i-shikwa (in English and Urdu), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-561324-7, ""Iqbal it is true, is essentially a poet of Islam ... the Islam which provided a new light of thought and learning to the world, and of heroic action and glorious deeds. He was devoted to the Prophet and believe his message." (from the foreword by Rafiq Zakaria, p. 9)"

- Kiernan, V.G. (2013). Poems from Iqbal: Renderings in English Verse with Comparative Urdu Text. Oxford University Press and Iqbal Academy Pakistan. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-19-906616-2. Quote: "In Persian, ... he published six volumes of mainly long poems between 1915 and 1936, ... more or less complete works on philosophical themes" (p. xiii)"

- Sevea, Iqbal Singh (2012), The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 14–, ISBN 978-1-107-00886-1, "Iqbal was elected to the Punjab Legislative Council in 1927 and held various posts both in the All-India Muslim League and the Punjab Provincial Muslim League."

- Kiernan, V.G. (2013). Poems from Iqbal: Renderings in English Verse with Comparative Urdu Text. Oxford University Press and Iqbal Academy Pakistan. pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-19-906616-2. Quote: "In Urdu, Iqbal is allowed to have been far the greatest poet of this century, and by most critics to be the only equal of Ghalib (1797-1869). ... the Urdu poems, addressed to a real and familiar audience close at hand, have the merit of being direct, spontaneous utterances on tangible subjects.

- McDonough, Sheila D (5 November 2020), Muhammad Iqbal, Encyclopedia Britannica, retrieved 7 February 2021, "He is considered the greatest poet in Urdu of the 20th century"

- Anjum, Zafar (13 October 2014), Iqbal: The Life of a Poet, Philosopher and Politician, Random House, pp. 16–, ISBN 978-81-8400-656-8, "Responding to this call, he published a collection of Urdu poems, Bal-e-Jibril (The Wings of Gabriel) in 1935 and Zarb-e Kalim (The Stroke of the Rod of Moses) in 1936. Through this, Iqbal achieved the status of the greatest Urdu poet in the twentieth century."

- Robinson, Francis (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press, pp. 283–, ISBN 978-0-521-66993-1, "In India, the ghazal and mathnawi forms were adapted in Urdu to express new social and ideological concerns, beginning in the work of the poet Altaf Husayn Hali (1837-1914) and continuing in the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938). In the poetry of Iqbal, which he wrote in Persian, to speak to a wider Muslim audience, as well as Urdu, a memory of the past achievements of Islam is combined with a plea for reform. He is considered the greatest Urdu poet of the twentieth century."

- Sevea, Iqbal Singh (2012), The Political Philosophy of Muhammad Iqbal: Islam and Nationalism in Late Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 14–, ISBN 978-1-107-00886-1, "In 1930, he presided over the meeting of the All-India Muslim League in Allahabad. It was here that he delivered his famous address in which he outlined his vision of a cultural and political framework that would ensure the fullest development of the Muslims of India."

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas; Hay, Stephen N.; Bary, William Theodore De (1988), Sources of Indian Tradition: Modern India and Pakistan, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-06414-9, "Sir Syed Ahmed had brought rationalism and the desire for knowledge and progress to the Indian Muslims; Muhammad Iqbal brought them inspiration and philosophy. Next to the Quran, there is no single influence upon the consciousness of the Pakistani intelligentsia so powerful as Iqbal’s poetry. In his own time, it kindled the enthusiasm of Muslim intellectuals for the values of Islam and rallied the Muslim community once again to the banner of their faith. For this reason, Iqbal is looked upon today as the spiritual founder of Pakistan."

- "Allama Iqbal: Pakistan's national poet & the man who gave India 'Saare Jahan se Achha'". ThePrint. 9 October 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Please visit Wikipedia for more references